Scandal erupted in a Philadelphia marketplace one Saturday morning in August 1839. Making his usual rounds to inspect the food for sale, the market clerk came upon a bench where all the butter weighed less than marked. With a flourish, he confiscated “lump after lump” before the crowds of shoppers. The butter vendor, or huckster, was an African American woman. She extended the public performance and “pounced upon the clerk like a wild cat.” After a brief tussle, she sat atop him and rubbed butter over his face, up his nose, and in his ears, inverting the familiar antebellum image of a white man pinning down a black woman to enact his carnal fantasies. Capping this reversal of racial and sexual authority, she grabbed a handful of her butter and taunted the clerk to “weigh my butter, if you can, puppy—and touch it, if you dare.” Lest the innuendo of an animalized black woman pinning down a white man obscure the moral, the Baltimore Sun newspaper columnist reporting on the event exhorted readers to watch out for swindlers.

The story almost certainly did not happen, at least not how the author told it. None of Philadelphia’s major papers carried it, but it circulated in newspapers of southern cities like Baltimore and Charleston. Hucksters—poor, often women, sometimes black—frequented streets and markets, buying unsold or second-rate food from farmers and selling it at a markup. For poorer consumers, hucksters offered a vital service. For the penny press’s middle-class audience, hucksters embodied three related threats: the transience of city life, food adulteration, and cross-class and interracial heterosociability. Connecting all three fears was promiscuity, a term that connoted not only sexual licentiousness, but also the indiscriminate and ungoverned mixing of people and things. In other words, middle-class critics viewed hucksters as crooks and sexualized threats, charges that undermined the legitimacy of huckster women and the cheap food they trafficked in.

Stories about hucksters appeared regularly in the emerging penny press of the antebellum period. These papers printed sensational tales both to moralize and titillate. Stories about hucksters were suffused with sexual slander and racial animosity. The vilification of the black huckster and her belligerent, butter-laden sexuality resonated with Philadelphians because it drew from a common set of narratives to describe both an increasingly visible figure in the antebellum metropolis, as well as the chaotic nature of urban spaces. In a sense, hucksters characterized the haphazardness of cities. Like most antebellum urbanites, hucksters were, according to the 1823 City Council Records, “unsettled and unknown.” They built networks without regard to their clients’ social positions, be they farmers, grocers, night watchmen, washerwomen, boardinghouse keepers, or brothel madams. They were out at all times of day and especially at night to corner arriving farmers for the best deals. And finally, they turned street corners, oyster dens, or wharves into temporary marketplaces. Being promiscuous was simply good business.

And yet, good business opened hucksters to middle-class critiques that linked transience with sexual danger. Those who moved about, the logic went, blatantly disregarded gendered proprieties and blurred race and class boundaries. Hucksters resembled another group who walked the streets selling goods and services: prostitutes. This was the subtext of an October 17, 1829 exposé of nocturnal Philadelphia that appeared in the Mechanic’s Free Press, where “Hucksters, Factory girls, and the deluded daughters of honest industrious mechanics” were described as “a promiscuous class of females, all huddled together in a mass” in dance halls with “Sailors, Raftsmen, Coalmen, and cut down Dandies.” Neither hucksters nor prostitutes confined themselves to lower-class neighborhoods, however. Their movements between patrician and plebeian spaces produced a shadow landscape of immorality. The two trades also symbolized the perils of unbridled commercialism, from downward class mobility to the notion that everything and everyone was for sale. Thus, hucksters and prostitutes served as foils for ascendant middle-class ideas about moral and commercial order.

Promiscuous hucksters also exposed the flimsiness of racial boundaries among the city’s laboring classes. Again, public moralists conflated sexual and commercial promiscuity. An 1806 petition, located in the City Council Records, implied carnality was hucksters’ primary commerce in a Baltimore market house, where “from 6 to 8 Lewd women and Black & White and some yellow & as many men of Different Caulers” met nightly to negotiate sexual favors with each other rather than the price of eggs with farmers. Interracial sex was an explosive social and political issue. Defenders of slavery and racial hierarchy manipulated it to promote segregation and delegitimize abolitionists, who, like hucksters and prostitutes, worked in mixed-race settings. Interracial sex did not merely pose a threat to the antebellum racial order, however; it was also an analogue for middle-class fears about the ungoverned circulation of money and goods in an urbanizing market society.

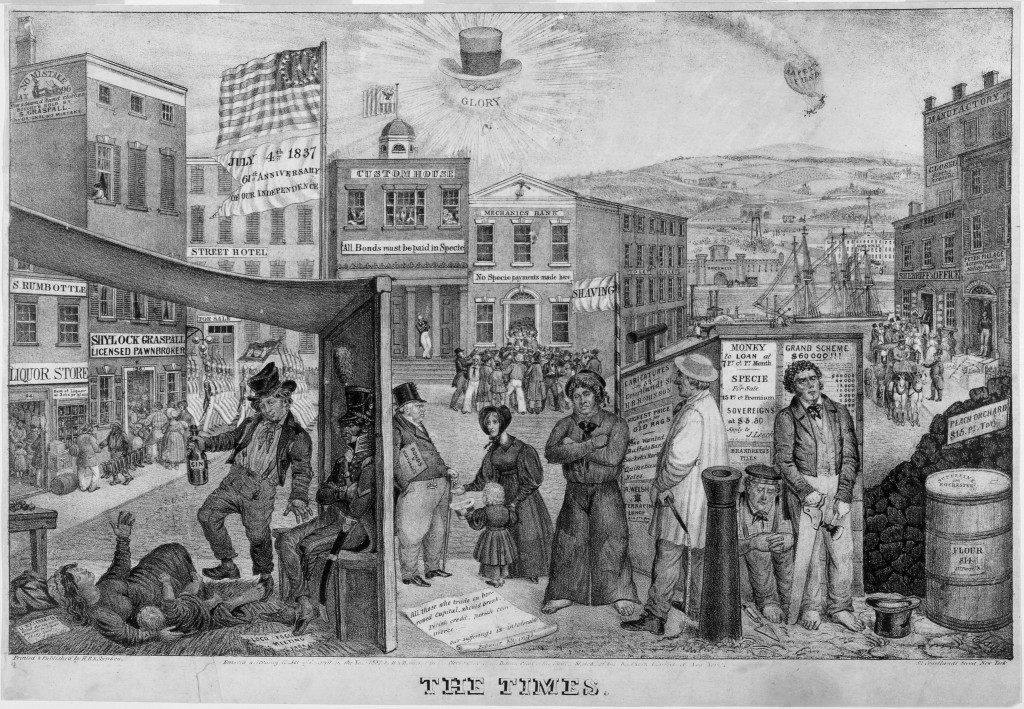

Antebellum visual culture captured these fears more vividly than writers of the time. For many artists, hucksters stood as easily recognizable symbols of the chaos of class, race, and gender relations under market capitalism. Well-known scenes of real or imagined urban America like George Catlin’s Five Points (1827) and Edward Clay’s The Times (1837) foregrounded women hucksters in the vortex of debauchery. In Clay’s lithograph, a huckster lies drunk on the ground as men leer at her upturned skirt. Catlin’s print caricatures race and class at New York’s most infamous crossroads, as a hunched-over white huckster serves corn to a black man and woman, swine run rampant, African Americans fight, and an ostensibly middle-class gentleman stands out of place amidst it all.

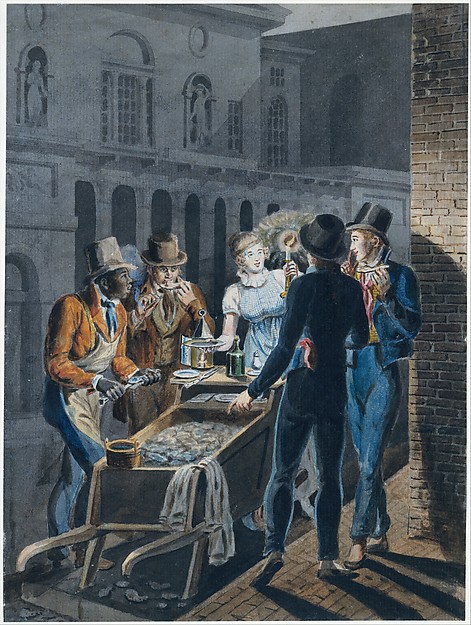

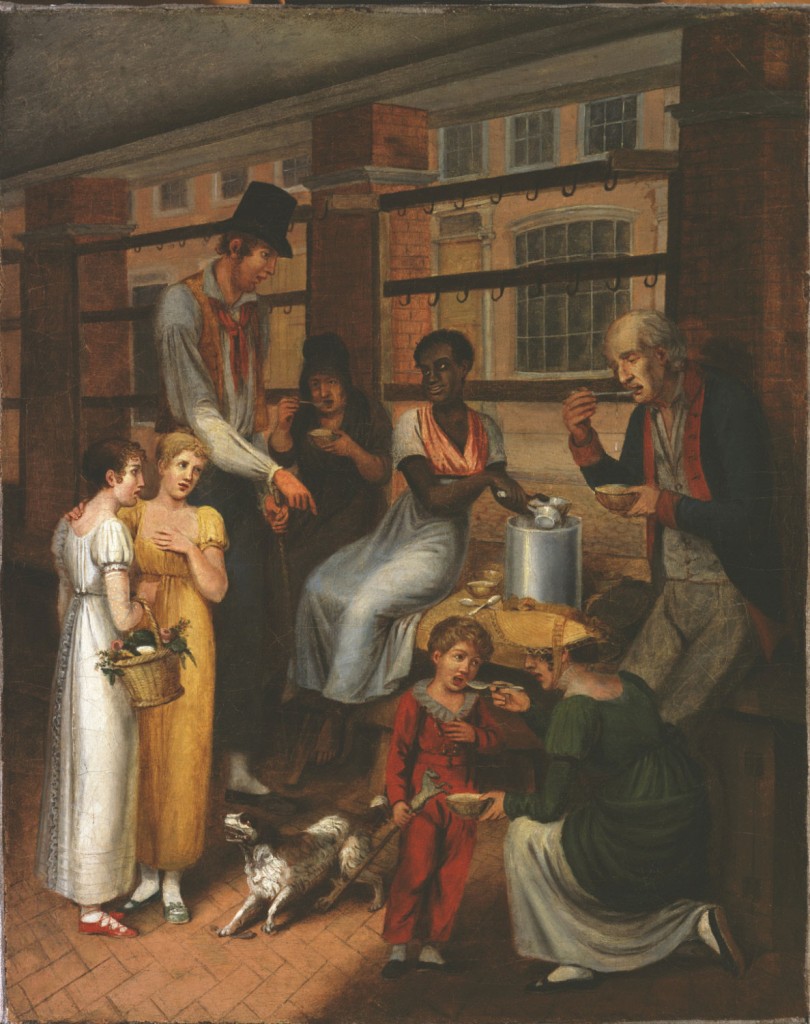

While middle-class moralists decried the market’s promiscuity, most Americans likely found the casual mixing of hucksters at Five Points alluring if not also unsettling. German artist, John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821), depicted this ambivalence in two works linking hucksters, promiscuity, and food. Nightlife in Philadelphia (c. 1811-13) meditates on how nighttime transforms patrician spaces like the front of Chestnut Street Theatre into plebeian ones. Krimmel spotlights a young woman and black oysterman serving three male dandies. The scene carries explicit sexual themes: oysters were common set pieces in paintings about sex, a young man is caught in the suggestive act of slurping, and the huckster’s confidence and presence in public at night likely conjured up images of prostitution for viewers. Krimmel’s Pepper-Pot: A Scene in the Philadelphia Market (1811) elaborates on similar themes. The title refers to the heavily spiced West Indian stew composed of vegetable and meat scraps. There is an implied parallel between pepperpot’s contents and the scene’s social makeup: male and female, young and old, polished and plebeian, white and black. While the scene must have been jarring for audiences that were increasingly concerned with their respectable, middling status, the lack of an overt critique implies Krimmel saw something liberating in this promiscuity.

Huckster women illustrate the double standards in nineteenth-century American constructions of sex, food, and capitalism. Promiscuity and geographic mobility were not problems for middle-class clerks and businessmen as they were for women. Likewise, economic critiques of huckstering veered into sexual slander in ways it did not for trades associated with men. That detractors like the writer of the opening story characterized huckster women as impetuous, pugnacious, and unladylike is unsurprising. Sexual vilification is common whenever women from a society’s supposed margins exercise power in a highly public trade. Male hucksters were not singled out to the same extent, which likely helped many of them to expand their business and shed the label of “huckster” for “grocer” or “broker.” Meanwhile, for women and African American hucksters, legal and cultural attacks continued to erode the status and viability of their trade, pressing many into even more precarious professions—like prostitution.

Robert J. Gamble is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at the University of Kansas. He completed his PhD in History at Johns Hopkins University in 2014 and is revising his first book, Civic Economy: Governing the Urban Emporium in the Early American Republic, which emphasizes the role of regulation in the development of capitalism and urbanism in the U.S. He contributed a chapter on secondhand goods to Capitalism by Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America, and he has a forthcoming essay on peddlers and itinerancy in the revolutionary mid-Atlantic. He is also at work on a history of lotteries, race, and statecraft in the long nineteenth century.

Robert J. Gamble is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at the University of Kansas. He completed his PhD in History at Johns Hopkins University in 2014 and is revising his first book, Civic Economy: Governing the Urban Emporium in the Early American Republic, which emphasizes the role of regulation in the development of capitalism and urbanism in the U.S. He contributed a chapter on secondhand goods to Capitalism by Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America, and he has a forthcoming essay on peddlers and itinerancy in the revolutionary mid-Atlantic. He is also at work on a history of lotteries, race, and statecraft in the long nineteenth century.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com