In anticipation of our forthcoming series on Histories of Religion and Sexuality, edited by Neil J. Young, this special issue brings together contributions from NOTCHES‘ catalogue that excavate the rich historical intersections of gay rights and religious institutions in the modern period. Placing these essays alongside each other offers a multinational perspective on the intertwined histories of religion and sexuality. At the same time, these essays clear a path away from simplistic narratives that understand religion as a reactionary or conservative force opposed to LGBT rights.

These essays do not argue that histories of religious conservative opposition to gay rights should be overlooked. Instead, these histories deepen our understanding of religious conservatism. T.J. Tallie and Jason Bruner explore the colonial and postcolonial roles of the Anglican Church and Catholic Church in Uganda and how each gave rise to anti-gay politics. Sean Brady and Chiara Beccalossi focus on the pivotal role of the Catholic Church in Ireland and Italy in opposing gay rights laws and activism. These essays reveal that different religious, intellectual, and cultural traditions informed Uganda, Irish, and Italian anti-gay activism and spotlight how regional differences play significant roles in the formation of religious and sexual politics. Importantly, these essays forestall a monolithic understanding of the Catholic Church’s sexual politics.

By focusing on conservative responses to gay rights, it might be easy to conclude that Catholicism (and perhaps organized religion itself) and gay rights have been opposing cultural forces across region and time. Jeffrey Meek’s essay, however, emphasizes how the Catholic Church in Scotland offered material support to gay rights groups after Scotland’s largest Protestant church soured on supporting gay rights groups engaged in law reform. This surprising history not only reveals the contingency of the relationship between Catholicism and gay rights but also the internal diversity of a single denomination.

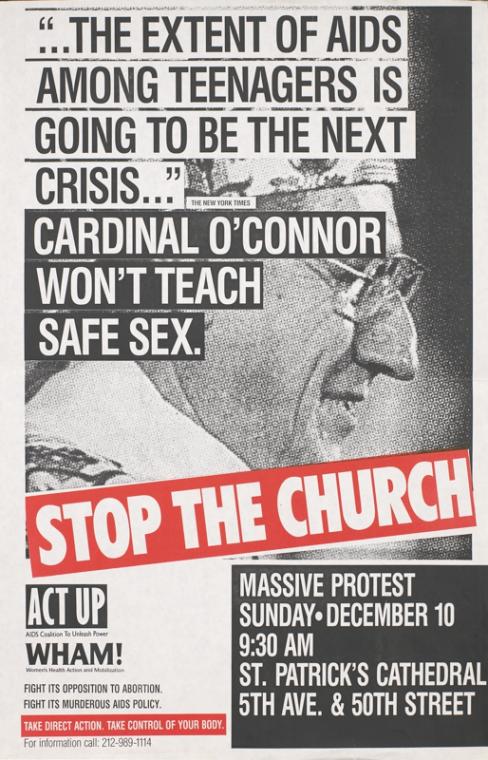

Likewise, in Lynne Gerber and Gillian Frank’s interview with Anthony Petro about After the Wrath of God, Petro underscores the need to analyze the broad range of religious responses to the emergence of AIDS in the United States in the 1980s and 90s. Petro examines how religious figures and groups closer to the American mainstream crafted positions that negotiated a fraught balance between compassion for the sick and concern over the perceived moral issues with which AIDS has long been entwined. This intervention foregrounds how evangelical and mainline Protestants and many Catholics actors, although differing “in their theological and moral approaches to homosexuality, tended to call for care and compassion and, eventually, for sexual abstinence and fidelity for people in paired relationships.”

This same attention to liberal and conservative positions within and across denominations is central to Heather White’s story about gay marriage and mainline Protestantism and Gillian Frank’s history of Jewish divisions over gay rights in the United States. By excavating the longstanding history of mainline Protestant support for gay rights and gay marriage, White challenges popular conflations of religion with sexual conservatism. At the same time, she calls attention to how denominations in the U.S. have been internally divided over marriage, ordination, and rights. Gillian Frank’s essay likewise shows how within and across denominations, Jews divided over gay civil rights ordinances in the 1970s United States. There was, he argues, little theological or popular consensus among Jews as to whether opposing or supporting gay rights was an authentic expression of Jewish values.

Together, these essays remind historians of sexuality that religions are not singular, monolithic, or unchanging. Rather, they are heterogeneous and politically diverse. Historians, in other words, should not assume that religious institutions have always been hostile to gay rights. Because religion does not carry within it a universal sexual politics, then it is imperative to ask after denominations’ changing stance on gay rights in different cultures or time periods.

Chiara Beccalossi, ‘Pray the gay away’: The Catholic Church, Sexology and Sexuality in Italy

Sean Brady, Ian Paisley (1926-2014) and the ‘Save Ulster From Sodomy! Campaign

Jason Bruner and T.J. Tallie, Truly Ugandan: Martyrs, Pope Francis, and the Question of Sexuality

Gillian Frank, The Yellow Star and the Pink Triangle: Judaism and Gay Rights in the 1970s

Jeffrey Meek, Homophile Priests, LGBT Rights, and Scottish Churches, 1967-1986

Anthony Petro with Lynne Gerber and Gillian Frank, AIDS, Sexuality and American Religion

Heather White, Mainline Protestants and the Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage

Gillian Frank is a Managing Editor of Notches: (re)marks on the History of Sexuality. He is currently a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion and a lecturer in the Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies at Princeton University. Frank’s research focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race, childhood and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently revising a book manuscript titled Save Our Children: Sexual Politics and Cultural Conservatism in the United States, 1965-1990. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com