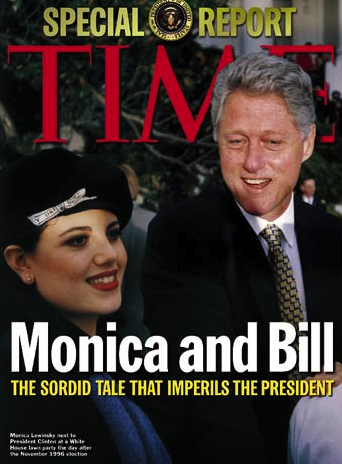

In 1998, the ABC newsmagazine Nightline fretted that the Clinton scandal with Monica Lewinsky would “come down to the question of whether oral sex does or does not constitute adultery.” President Bill Clinton, supposedly, had told Lewinsky that oral sex could not be adultery. He had told Gennifer Flowers the same thing, according to state troopers in Arkansas in 1992. Making this distinction between oral sex and adultery was also part of President Clinton’s legal strategy in his multiple sex scandals. It seemed to many Americans that Bill Clinton had reached a new nadir of political double-speak and lies. But Clinton was not the first philandering spouse to attempt to distinguish oral sex from adultery. Instead he was taking advantage of a legal definition of adultery that emerged from the post-World War II system of fault divorce, which held that only vaginal sex counted as adultery. Under this legal regime, men and women could engage in a range of sex acts, which the courts recognized as sodomy, and still maintain that they had not technically cheated.

Until the 1970s, to get divorced, an innocent spouse had to prove that his or her wife or husband had violated their marriage vows. Judges, not spouses, determined whether a breach met the standard of a set of divorce “grounds” established by state legislatures. In other words, a spouse could successfully fight to stay legally married by denying fault under the prescribed grounds. Some states had loose and flexible grounds for granting divorce—notably Nevada, which allowed for divorce in cases of mental cruelty, separation, insanity, and more. Others had strict grounds such as New York, which allowed divorce only in the case of adultery.

When it came to adultery under the postwar fault divorce legal regime, only extramarital vaginal sex counted as cheating. Every other sex act counted as sodomy or crimes against nature. As one Nebraska judge stated in 1958, “Our statutes classify sodomy under ‘Crimes against nature.’ … The decisions all agree that sodomy is not adultery. All agree that it may constitute cruelty.” This separation of sodomy from adultery enabled husbands who engaged in a range of sex-acts with men or women to claim that they had not committed adultery. Clinton’s rationale fell squarely within this long tradition of only counting vaginal penetration as sex.

In the case of same-sex philandering husbands, many fought their wives’ attempts to divorce them by denying that sodomy was adultery. It’s not always clear why they wanted to remain married. Maybe they wanted to keep any mention of their sexual activities out of official court records, to maintain the respectability that gay men did not possess during this era, or just to hang on to their home lives. Perhaps they did not want to pay alimony to their ex-wives. No matter their motives, these husbands resisted the divorces their wives sought. And some did so by claiming that sodomy—which could refer to oral sex or anal sex—was not adultery.

Clinton’s constituents in the 1990s may not have seen a distinction between sodomy and adultery, but judges in the postwar period did. To give just one example, in 1951 New Yorker Louis Cohen crossed the Hudson River for a dalliance with another man in New Jersey. After police caught Cohen in this sexual encounter, the New Jersey court convicted him of “the crime of sodomy upon a male person” and sentenced him to jail for no fewer than seven years. His wife Ruth Cohen filed for divorce in New York, where the couple resided. New York allowed for divorce only in the case of adultery, and Ruth Cohen felt that her husband’s conviction clearly indicated he was guilty of infidelity. The Supreme Court of New York, however, disagreed. It ruled “the words ‘sexual intercourse’ do not include the acts of carnal knowledge coming within the scope of the definition of sodomy” and cited British, Alabama, and North Carolina law for categorizing sodomy as distinct from adultery in their fault divorce statutes. The New York Supreme Court justices ended the ruling by explaining that they were sympathetic to Ruth Cohen but powerless to act on her behalf because of the law. Ruth Cohen remained unhappily married to her jailed husband.

Ruth Cohen’s situation was rare, but she was not alone. Other women in New York encountered the same difficulties when their husbands cheated with other men. We cannot know how many women remained in their marriages because lawyers told them they had little chance of winning their case, but legal aid clinics throughout the state reported these cases to the New York legislature. In one particularly heartbreaking situation, a woman could not even get a divorce after her husband had sexually assaulted their son. An assault on a daughter, however, would have allowed a divorce; that would have been recognized as “real sex” and therefore as a form of adultery.

The Cohens’ case had implications for women engaging in straight acts of infidelity. In 1967, a husband sued his wife for divorce in New Jersey claiming that she had committed adultery. The defendant wife denied that she had intercourse and established through the testimony of her gynecologist and through hospital records “that due to X-ray treatment for carcinoma of the cervix, her vagina was completely occluded and… not the slightest degree of penetration was possible.” The court dismissed the aggrieved husband’s divorce complaint, finding that sexual activity other than vaginal intercourse was not adultery. These cases partly reflected how difficult it could be to win a divorce in the postwar era. But it also revealed a consensus among many judges in states such as California, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania who maintained a narrow legal view of what counted as sex while arguing that sodomizing husbands and wives should remain married.

By the late 1960s, most state legislators became skeptical that sodomy was not adultery. The New York legislature passed a law defining sodomy as adultery in 1966. Just a few years later, beginning in 1970, most state legislatures simply implemented no-fault divorce, which allowed anyone out of his or her marriage on demand. For most Americans, the definition of adultery became an emotional rather than a legal matter. But Clinton seems to have continued to approach adultery with the same narrow legal definition that reigned supreme before 1970. Certainly Clinton was a lawyer and may have approached all things from a legal perspective. But he also hailed from Arkansas, one of the few states that maintained fault divorce. To this day, the easiest way to get divorced in Arkansas is still on the grounds of an 18-month separation. The man who signed this modest liberalization of divorce into law in 1991 was William Jefferson Clinton.

In the postwar period some men and women had the unique ability to reframe adultery as sodomy in order to keep their marriages. In the 1990s, Clinton could and did think in these terms about marriage, its obligations, and the sexual privileges within and outside of it. Long after the postwar period ended, Clinton’s retention of this fault-divorce worldview helped him greatly. When Clinton claimed this privilege, he not only kept his marriage, but also the White House.

Alison Lefkovitz is an assistant professor in the Federated History Department at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers-Newark. She is currently serving as the Center for Historical Research Junior Fellow at Ohio State University, where she is working on her book manuscript The Politics of Marriage in the Era of Women’s Liberation.

Alison Lefkovitz is an assistant professor in the Federated History Department at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers-Newark. She is currently serving as the Center for Historical Research Junior Fellow at Ohio State University, where she is working on her book manuscript The Politics of Marriage in the Era of Women’s Liberation.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

So interesting! Thank you so much. It amazes me how similar some of these twentieth-century views regarding definitions of sexual relationships used during the middle ages. In European Christendom it was not divorce that prompted consideration of whether or not an act was sexual or not, it was confession and its corresponding penance. The manuals for confessors can get very technical regarding what constitutes a sex act and whether or not it is a sin or how grievous a sin.

It is not so much that what we in the 21st-century accept encompasses a wider array of sexual possibilities (an idea that leads to statements like that of Dan Savage who equates the views of those against gay marriage to the thinking of medievals or allows the homophobic person to imagine that if a society allows homosexuality then pedophilia and bestiality are sure to follow as acceptable); it is that all the parts are there but their significance is imbued from a different well of ideas. hmmm. The meanings are different. Like, the philanderer who in the movies tries to explain, “But it didn’t mean anything!” Where is the meaning coming from for these different systems?

This has certainly given me a lot to think about!

Thanks.