Interview by Justin Bengry

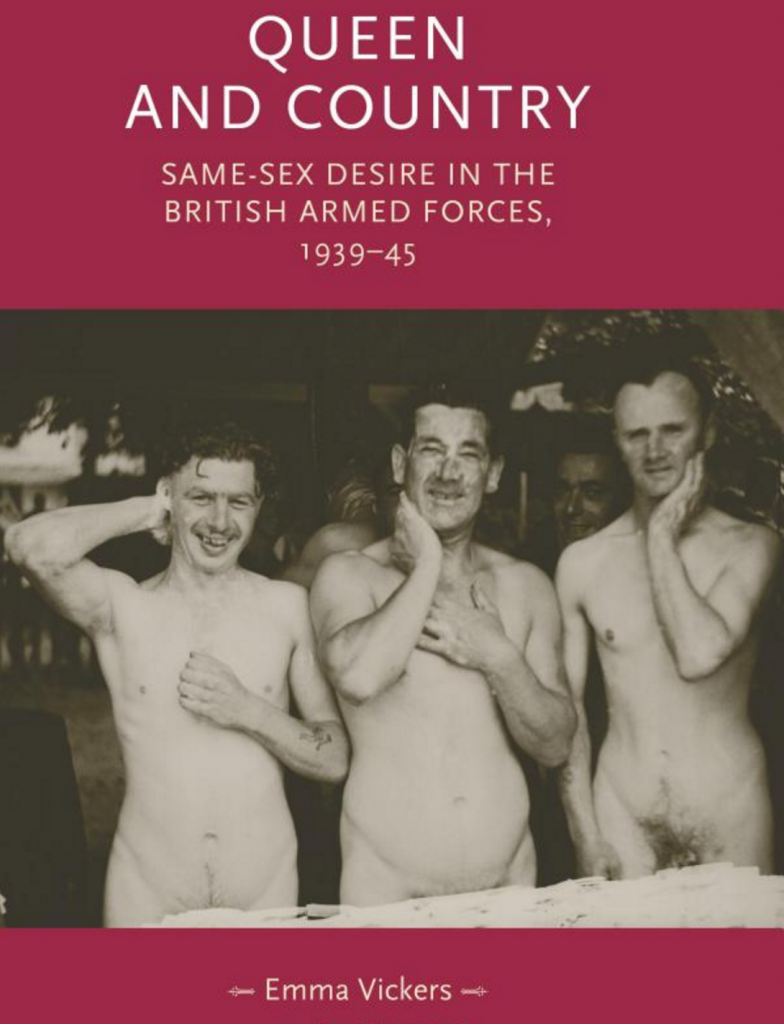

Historians have long recognised the impact that war and conflict have had on queer identities and communities. It has been more than a quarter century, in fact, since Allan Bérubé’s now-classic study Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two revealed the previously unwritten wartime history of gay men and lesbians in the United States. And yet, in the UK at least, despite the profound power and myth surrounding the experience of war that pervades understandings of the country’s past, and indeed its present, no single book addresses the country’s queer past in wartime. Emma Vickers’s Queen and Country: Same-Sex Desire in the British Armed Forces, 1939-45 explores the experience of wartime for gay men and lesbians, the ways in which they navigated their lives within the context of mandatory homosociality and heightened surveillance, and how they could be integrated into new communities of servicemen and servicewomen despite official hostility directed toward same-sex love and desire. Vickers’s deft employment of oral histories also offers insight in even more personal ways to the myths and memories of wartime, challenging queer and non-queer readers alike to reevaluate their understandings of the UK’s wartime past.

Justin Bengry: How would you characterize queer identities in Britain before the Second World War?

Emma Vickers: I would say that there was still a very strong distinction between acts and identities that didn’t exist in the same way after 1945. British society was knowledgeable about same-sex desire, not least because of the tendency of the press to discuss the activities of priests and scout masters for example. When Britain went to war in 1939, queer identities were pluralistic and socially and geographically diverse. The most visible archetypes were obviously the effeminate queen and the masculine woman, yet many people were experimenting with members of the same sex and refusing to align their identities to that activity.

JB: What impact did the influx of American soldiers have on queer Britons? Was the UK unique compared to other areas of wartime mixing and disruption?

EV: American soldiers had a huge impact on queer life during the war. Quentin Crisp gives a lovely account of the American Forces ‘flow[ing] through the streets of London like cream on strawberries.’ They often mistook Crisp for a woman but ‘allowed themselves to be enlightened with no display of disgust.’ In this sense, American soldiers brought with them new bodies and new attitudes towards sex. It’s reported that they raised the prices of rent boys and that most possessed a healthy attitude towards same-sex desire. For men like Crisp, the presence of the Americans was a boon. They helped to create a sense that life and its pleasures were ephemeral and that chances ought to be taken. I also believe that American soldiers gave Britons a taste of another country, one that many men would explore through bath houses and bars in the post-war period.

JB: Was there a particular wartime queer masculinity?

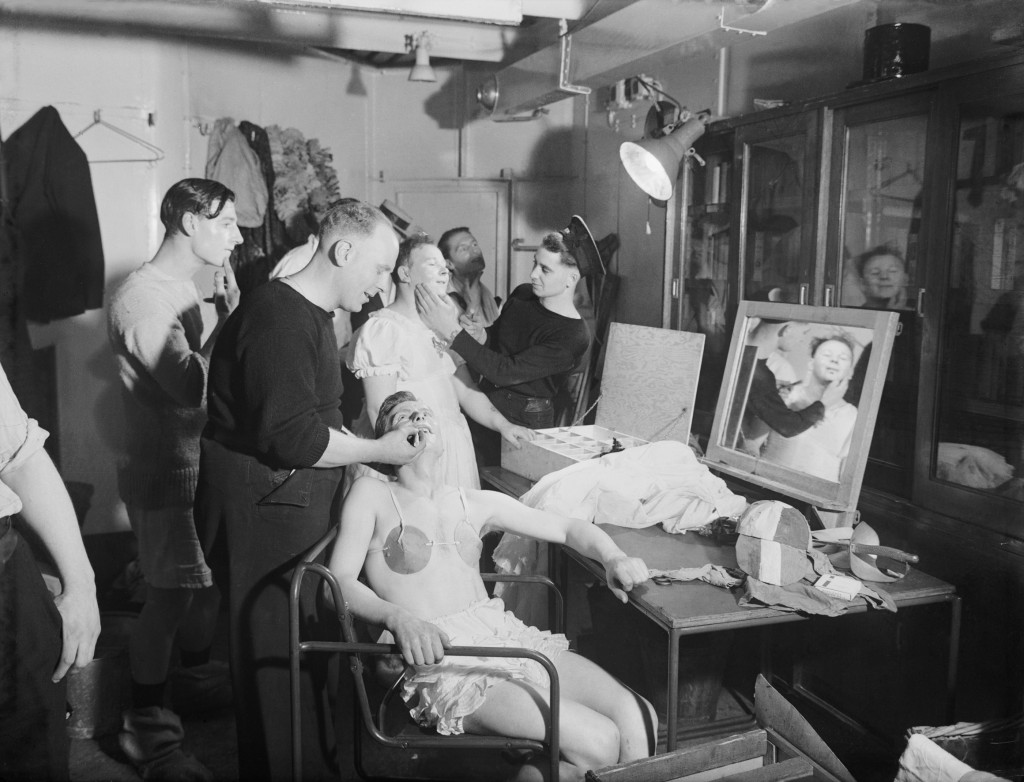

EV: There were many, I’d say, ranging from the outwardly heteronormative queer man to those who inscribed their sexuality more visibly on their bodies. Some queer men who were open about their sexuality often felt that they needed to be overly masculine and prove their worth in ways that others did not. There was certainly more variety when it came to queer masculinities during the war than in the post-war period.

JB: Does the power of ‘wartime sacrifice’ sufficiently explain servicemen’s lack of resentment toward the state which criminalised their desires? What else might explain this (if it needs further explanation)?

EV: That goes some way to explaining it. I think queer men were used to quietly subverting the state and its laws rather than confronting it directly. The law was so deeply entrenched in their lives that most lived with it and never thought to question it. I suppose you could say that queer men were resigned to the conditions. More than anything, the veterans that I interviewed were keen to expose the hypocrisy of the Armed Forces rather than the unjustness of civilian law. Moreover they were just as attuned and susceptible to discourses of wartime patriotism as the next person and so the state’s criminalisation of their desires just didn’t figure unless they were caught out. Some queer men even saw the law as an important player in shaping the contours of queer culture and adding frisson to their encounters. Many revelled in their own rebelliousness and resented the advent of the Sexual Offences Act in 1967 for taking some of that danger away.

JB: How was queerness (or suspicion of queerness) constituted differently for men and women in the services?

EV: For both men and women it came down to the need for absolute proof. There was a stock phrase that I read quite a few times and that was ‘confirmed’. Officers in both the male services and the auxiliary services were often happy to accept activity that was justified as being borne out of desperation or youthful experimentation. Passive male victims that ‘would not repeat the offence’ were also seen as worthy of retention. There was a genuine belief that queerness could be eliminated by three square meals and a bit of military discipline. For those who were ‘confirmed’ their behaviour had to be considered to be disruptive before they were disciplined. And of course there were those men and women whose queerness was an instrumental part of their service, like Dennis Prattley who was a sexual surrogate for his shipmates. There were countless men like Prattley whose queerness was well-known yet they proved themselves to be indispensable members of their units and so were retained, despite the illegality of their desires.

Of course, the consequences for men could be catastrophic; buggery could result in life imprisonment and there are so many cases in the courts-martial registers of men who have been caught out together. For women, bed sharing and hand holding were seen as working class practices and at worst, women were dismissed from service if they could not be reposted. It’s worth remembering that there was a huge difference between what the law decreed and how it was implemented. In some ways, this flexibility marked out the services as unintentionally progressive.

JB: How does your story contribute to recent studies in queer history that challenge the stability of sexual identities before the 1960s?

EV: I think my work proves that there was no stability. During the war, same-sex activity between men and between women was part and parcel to life. It was only after the war that identities began to solidify. The story that I like to tell relates to an interviewee of mine that responded to an appeal in Gay Times. His identity was totally fluid. He had relationships with men during the war and married a woman after he came out of service. Following the death of his wife he resurrected his interest in men. It’s so important that we listen to the experiences of people like this and avoid over-theorising their lives.

JB: Whose stories were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

EV: One of my biggest regrets is that I wasn’t able to interview any women for the book. I think this has something to do with contemporary labels and the fact that same-sex desire between women has never been illegal in the same way that it was for men. I think this might have influenced their willingness to ‘expose’ the Armed Forces in the same way. There was something very political about the way that some of my male interviewees approached our interviews. I’d have also liked to have heard some first-hand accounts from those men who were described by my interviewees as ostensibly ‘straight’ yet who conducted sexual relationships with them during the war. Finally, given the way that my research is currently moving towards looking at trans* lives in the British Armed Forces, I regret that I didn’t frame the experiences of those individuals when I wrote my PhD.

JB: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

EV: I’d love to see a redacted version being used in primary and secondary curricula although that’s very ambitious! In higher education I think it stands as a good example of how to search for a needle in a haystack so it ought to inspire hungry postgrads and undergrads alike. In the classroom I would use it alongside Allan Bérubé’s Coming Out Under Fire, Paul Jackson’s Canadian study, One of the Boys: Homosexuality in the Military During WWII and Yorick Smaal’s new work, Sex, Soldiers and the South Pacific, 1939-45: Queer Identities in Australia in the Second World War. For work that expands upon the conceptual framework that I use I would also vote for John Howard’s Men Like That: A Southern Queer History and Elaine Ginsberg’s work, Passing and the Fictions of Identity. Although Ginsberg’s work refers to African Americans passing as white, passing is a great concept for understanding how some men and women survived in the services.

Emma Vickers is a senior lecturer in History at Liverpool John Moores University. Her first monograph, Queen and Country: Same Sex Desire in the British Armed Forces, 1939-1945 (MUP 2013) explores the complex intersection between same-sex desire and service in the British Armed Forces during the Second World War. Emma has published articles in the Lesbian Studies Journal (2009) and Feminist Review (2010) and is currently working, with Corinna Peniston-Bird, on the edited collection, Lessons of War (Palgrave, 2016), which evaluates how gender history contributes, nuances and challenges existing understandings of the Second World War. She is also working on Dry Your Eyes Princess, a project which uses oral testimony to uncover the experiences of trans* personnel in the British Armed Forces before 2000.

Emma Vickers is a senior lecturer in History at Liverpool John Moores University. Her first monograph, Queen and Country: Same Sex Desire in the British Armed Forces, 1939-1945 (MUP 2013) explores the complex intersection between same-sex desire and service in the British Armed Forces during the Second World War. Emma has published articles in the Lesbian Studies Journal (2009) and Feminist Review (2010) and is currently working, with Corinna Peniston-Bird, on the edited collection, Lessons of War (Palgrave, 2016), which evaluates how gender history contributes, nuances and challenges existing understandings of the Second World War. She is also working on Dry Your Eyes Princess, a project which uses oral testimony to uncover the experiences of trans* personnel in the British Armed Forces before 2000.

Justin Bengry is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the project Queer Beyond London at Birkbeck College, University of London and researcher on the Historic England LGBTQ heritage and mapping project, Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Capitalism and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

Justin Bengry is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the project Queer Beyond London at Birkbeck College, University of London and researcher on the Historic England LGBTQ heritage and mapping project, Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Capitalism and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com