The Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) has held every fourth meeting outside the United States since 1992. The first Asia-based meeting was held in the technology-rich city-state of Singapore at the National University of Singapore, Tembusu College. The conference location drew many historians of technology based across South and East Asia who were attending SHOT for the first time. Seven of the conference sessions, including two roundtables and the keynote address by Ruth Schwartz Cowan, focused on the history of technology as it intersects with histories of gender, sexuality, and reproduction. The gender- and sex-related content of the conference indicates the growing interest of SHOT members in these themes, along with the rich histories of reproductive technology across the Asian world. Holding the conference in Asia provided an opportunity for Asia-oriented scholars of those intersections to meet and more broadly, to shift SHOT’s largely Western focus eastward.

On the last day of the conference, there were back-to-back panels on the history of reproductive technologies in Japan and China with the theme “Rethinking Reproductive Technologies and Modernities: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Reproduction in East Asian Societies, 1800s–2000s,” organized by Suzanne Z. Gottschang and Gonçalo Santos. Together, the papers on these two panels raised questions about how national and state policies, religious and cultural beliefs, and perceptions of medical modernity shape access to and perspectives on the use of reproductive and childbirth-related technologies.

The Japan-focused panel ranged across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, beginning with Izumi Nakayama’s paper on infertility in Japan, 1880–1925, and Shirai Chiaki’s paper on artificial insemination in Japan, 1890–1948. The second set of papers, by Azumi Tsuge and Gangé Nana Okura, centered on more recent Japanese history: Tsuge investigated ideals and practices related to motherhood and prenatal testing (especially amniocentesis) from the 1990s–2000s, and Gangé discussed more current cultural ideas and practices around fertility, as more and more Japanese women are waiting until their late 30s or 40s to start trying to get pregnant. Shirai highlighted the ways that traditional medicine identified infertility as a lack of vital energy and an indication of excessive male masturbation (and in the twentieth century, infection with a venereal disease). Artificial insemination practices throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries illustrate shifting ideas of gender, nationality, and Eastern understandings of bodily health, as well as what it meant to adhere to “natural” forms of conception, pregnancy, and birth. These practices also demonstrate the different ways that Japanese physicians engaged with translations of Western medical texts and used them to formulate frameworks for their own patients’ fertility treatment.

The China-focused panel emphasized pregnancy and childbirth. Zhu Jianfeng addressed the Cradle Project, a fetal development project and infant health plan designed to produce “super babies.” The Cradle Project was based on a tradition of spiritual cultivation and physical and mental fitness reinvented in the 1990s in order to support fetal education and to promote ideals of motherhood. Santos described and interpreted his findings from fifteen years of interviews on pregnancy and childbirth with women in Northern Guangdong. The sharp rise in caesarean births in the 2000s–2010s illustrates generational differences between the home birth and midwifery practices used by older women and the caesarean seen as physical markers of modernity for younger women. Gottschang focused on the sharp decline in maternal mortality rates at Beijing Maternal Hospital, indicating the rise of biomedicine in framing childbirth practice. Chen-I Kuan’s paper showed that the sharp rise in Chinese caesarean rates was also true in Taiwan, marginalizing midwives and promoting the idea that caesarean is the “healthiest” way to give birth. All of these papers demonstrated how Chinese and Taiwanese women in the recent past and present wrestle with how to incorporate “modern” and/or reinterpreted “traditional” Chinese medicine into their pregnancy and childbirth experiences.

Further comparative studies between China and Japan—along with other countries—would add more intricacy to the history of reproductive technologies and their interrelationship with ideas and ideals of gender and sexuality. For historians of sexuality, these panels also underscored the importance of continuing to study how cultural perceptions and the availability of technologies affect their efficacy and use. There is a rich and open field for scholarship on the ways that nationalism, rural/urban divides in technological access, and differences in traditional and modern medicine affect idealized perceptions and realities of pregnancy, childbirth, and reproductive health in Asia and beyond.

Finally, the conference also provided ample opportunities to share research ideas and make personal connections with scholars interested in related topics, especially through the interrelated special-interest groups Exploring Diversity in Technology’s History (EDITH) and Women in Technological History (WITH). There were also two roundtables: a practitioner’s roundtable, “Challenges and Opportunities for Working at the Intersections of Technology, Gender Equality, and Youth Empowerment in the 21st Century,” and a president’s roundtable, “Why Feminist Perspectives on Technology Still Matter—A Global Conversation.” The second roundtable included a historiography of feminist technology studies from Arwen P. Mohun; an overview of efforts to make women and feminism visible in Asian technoscience from Chia-Ling Wu; and ideas on reworking the perception that outsiders need to “introduce” African women to technology from Laura Ann Twagira. The conference room was overflowing, which indicated the wide and ongoing interest in feminist approaches to the history of technology and—lurking under the surface—a desire to combat lingering sexism and the diminution of feminist voices in the field.

The keynote address and the presidential address both highlighted the importance of gender, sexuality, and reproduction to the history of technology. Cowan’s keynote address focused on how gender ideals structured paid and unpaid work in Cuba, and she linked the relationship of socialist governing to the nation’s patterns of gendered work. The current SHOT president Francesa Bray stated in her presidential address that this first SHOT meeting in Asia should be only the beginning of deeper engagements with Asian and global histories of technology. Hopefully, the meeting has inspired other historians, as it has me, to explore in more depth and breadth the interconnected, international gender- and sex-related questions raised at SHOT 2016.

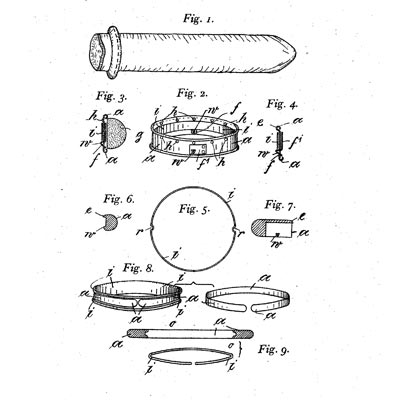

Donna J. Drucker is Assistant Director of the Office of Scholarship and Research Development at the Columbia University School of Nursing. She is the author of The Machines of Sex Research, The Classification of Sex, Contraception, and Fertility Technology. She tweets from @histofsex

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com