Coming out was one of the core values of the gay liberation movement in the early 1970s, but coming out at work generated a host of problems.

A series of sackings in England in the mid-seventies made it clear that coming out at work was going to be a contested area. Louise Boychuk was dismissed in 1975 by a London insurance brokers company for wearing a ‘Lesbians Ignite’ badge to work. Lesbianism had never been criminalised and, as reported by Margaret Coulson in Gay Left, her letter of dismissal explained that she was being sacked for ‘displaying a wording at our place of business which is distasteful to others and which could be injurious to our best interests if observed by clients whose goodwill results in the earning of large amounts of overseas currencies beneficial to our country.’ She lost her case at an industrial tribunal and they went so far as to cite the Book of Genesis to justify their decision.

There may have been some liberalisation of attitudes about sexuality since the so-called Swinging Sixties and the partial de-criminalisation of male homosexual activity, but the forces of bigotry remained powerful in the world of labour relations. There were other similar cases: a male teacher in a girls’ school in the Inner London Education Authority; a male trainee manager in British Home Stores in Worthing; a female bus driver in Burnley. The grounds for dismissal of each employee were their openness, rather than their sexuality itself.

Trade unionists, such as myself, who had been involved in the gay liberation movement and were committed to the concept that ‘Gay Is Good,’ began to form support groups in relation to the principle of coming out at work. Unbeknown to us, there were similar developments in the US. Members of such groups saw their sexuality as something not to be ashamed of; hiding one’s sexuality and lying about it were damaging to the individuals themselves and inhibited all their social interactions, whether at work or at home.

Trade unions found this openness more difficult to accept because they interpreted attempts at self-organisation by minority groups and women as being divisive. Such groupings were felt to run counter to the concept of ‘An Injury To One Being An Injury To All.’ The general secretary of the Confederation of Health Service Employees (COHSE) articulated this view very clearly when he wrote, in response to a survey from the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE): “In fact, we do not have heterosexuals or homosexuals in membership – we have members. And as far as we are concerned they are all people doing their best in their own way to be efficient at their work and make a contribution to society, and are entitled, when it is requested, to the services of the union.”

A number of union conferences, however, passed anti-discriminatory policy resolutions in this period. Many activists were more than willing to distance themselves from the bigotry of the Bakers Union leader who had asked the CHE if they wanted equality with ‘pigs or dogs’. These resolutions tended to be very Wolfenden-inspired insofar as they regarded gay people as victims rather than agents of change. There was a lack of vision about how to make these policies meaningful to the working lives of union members. Some of us became frustrated by the way such resolutions gathered dust in union filing systems.

While there was a growing acknowledgement that gay people experienced prejudice outside the workplace, there was difficulty in developing a shared language to incorporate challenges to such prejudice into the common sense of trade unionism. The closet had traditionally led to gay people separating the personal side of their lives from the more public worlds of employment, community involvement and political activity. In trade unions in the late seventies, the closet may have changed its appearance but it was still deeply entrenched.

The unofficial gay group in the union of which I was a member, the National Association of Teachers in Further and Higher Education (NATFHE), was pleased to be able to play a part in unblocking this political logjam. The union leadership had decided to hold the 1980 annual conference in Scarborough despite the fact that there was a campaign to boycott the town over its refusal to hire out its conference facilities to CHE. It should have been a straightforward case of showing solidarity, as some other unions had done, with an organisation which had been prevented from exercising its right to assemble.

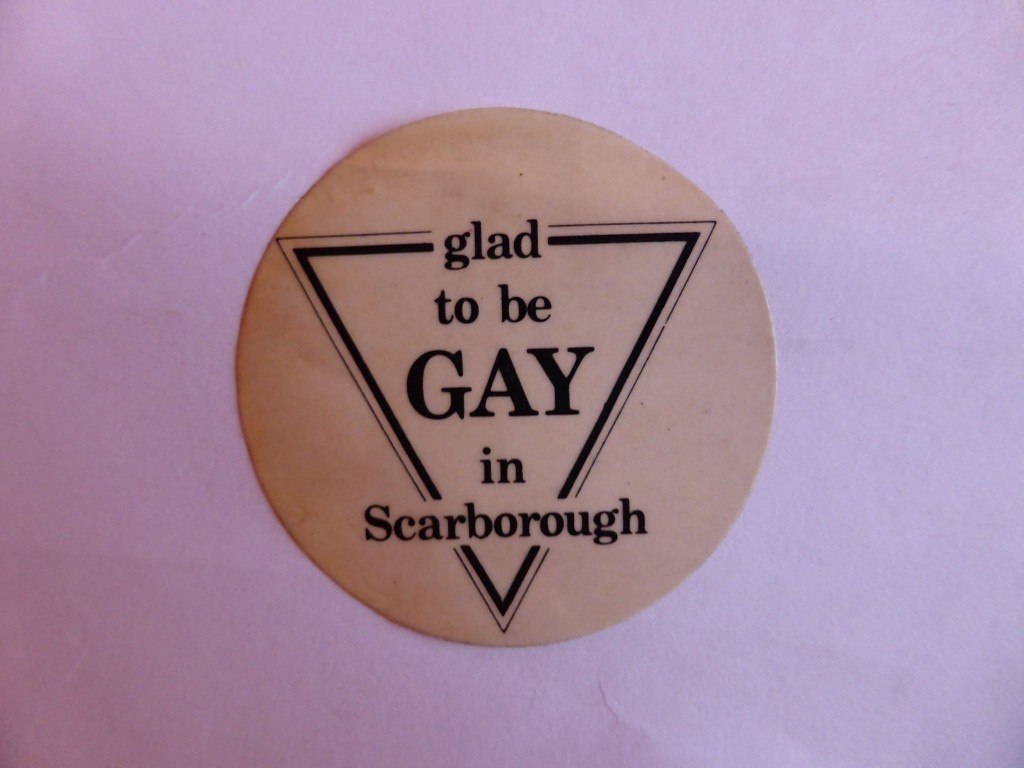

The gay group and its allies raised this issue and, after failing to make any progress through normal channels, we agreed to express our solidarity with CHE by using some of the more playful, zapping, street theatre tactics of the gay liberation movement at the opening of the conference. We distributed stickers saying ‘Glad To Be Gay In Scarborough’ and delegates were given song sheets containing the words of the Tom Robinson song ‘Glad To Be Gay.’ When the mayor rose to make his welcoming address, three of us unfurled the Gay Teachers Group banner and half the conference participants began singing. It was enormously embarrassing for the union leadership, particularly when a local newspaper reported our protest with the headline: ‘Gays Are People Too.’

Emboldened by our success at the conference, the gay group went on to organise a lobby of NATFHE’s quarterly National Council meeting to protest about the four years of inaction since the anti-discrimination policy had been agreed. Gay issues began to be taken more seriously: there were regular policy debates which reflected the everyday concerns of the gay membership and an inclusive approach was taken with more traditional bread and butter issues such as pensions. A key factor in these developments was that the initiatives had come from union members themselves and, while the playful gay liberation tactics had come from a tradition not normally associated with trade unions, the fact that the participants were union members had helped to break down the power of the closet in the union itself.

This interweaving of varying political strands of coming out, challenging the power of the closet, expressing solidarity with other struggles and re-examining the core values of trade unionism continued throughout the 1980s. In particular, this process of interweaving manifested itself in relation to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the impact of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) and the parliamentary attempt to criminalise the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in Section 28. Trade unions had been given the opportunity to widen their activities beyond the perceived concerns of married male breadwinners and, as a result, the representativeness of the whole union movement was greatly enhanced.

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com