Interviewed by Heike Bauer and Jana Funke

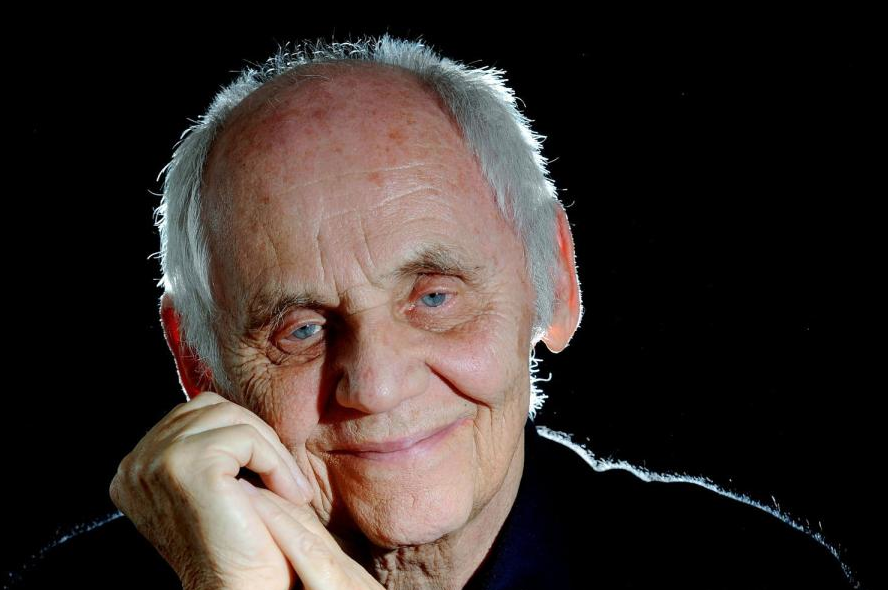

Erwin J. Haeberle is the founder of two archives – the “Haeberle-Hirschfeld-Archive” and the “Archive for Sexology” – which between them constitute one of the most significant collections of sexological work and related materials available.

Initially a literary scholar in the 1960s, Haeberle’s discovery of the existence of “sexual science” led him on an intellectual and archival journey that would take him from Germany to the U.S. (and back again). Via the universities of Heidelberg, Cornell, Yale and Hawai’i, he came to the Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality in San Francisco where he wrote The Sex Atlas (1978), a textbook aimed at students of sexuality, which was translated into German, Dutch, and Turkish. He also curated an exhibition on the birth of sexology (1908-1933), which was first shown at the World Congress of Sexology in Washington, D.C. in 1983. During the 1980s Haeberle dedicated himself to AIDS scholarship and activism at universities in San Francisco, Kiel (Germany) and Geneva. He worked as an advisor to the German government before taking up a post at the AIDS Center at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin in 1994. It was here that he built up both the print and electronic archives of sexology. Haeberle would donate the print archive to Humboldt University in Berlin where it is now accessible via the university’s central library as the “Haeberle-Hirschfeld-Archive”. The privately financed electronic archive, still called “Archive for Sexology”, is open access and has been maintained by Haeberle himself since his retirement in 2001.

Bauer and Funke: Tell us about your sexological archive. When did you first start to collect? How did you go about finding and collating the material?

Erwin Haeberle: When I began thinking about writing a history of sexology, I started by asking older colleagues about their memories and possible historical materials they might have saved. My first big success was a visit with the then 97-year-old Harry Benjamin in New York, who became a good friend and gave me all of his papers (he died at age 101). Through dogged detective work in the US, Germany, Switzerland, and Israel, I then found and met Herbert Lewandowki, the sons of Iwan Bloch, Max Marcuse, Felix Theilhaber, and Bernard Schapiro, the nephew of Albert Moll, the widow of Ludwig Levy-Lenz, and the American translator of René Guyon. They all told me personal details about the early pioneers in our field and gave me the memorabilia and other materials still in their own possession.

B&F: What were the practical challenges of establishing and continuing your archive?

EH: I never had any problems at all with my print archive and my collections. They were first supported by the Robert Koch Institute and then gladly accepted as a personal donation by Humboldt University in Berlin. In contrast, I am having enormous problems with my open access electronic archive, which I am forced to finance out of my own pocket. No university, organization or foundation has ever shown the slightest interest in it. Neither did any of them demonstrate the will and capability of taking it over and running it as intended. This is very strange indeed because it is, as stated on its homepage, “The World’s Largest Web Site on Human Sexuality”. In short: While there is nothing like it on the internet, I have never succeeded in finding financial support for the electronic archive. Indeed, since my own money is now running out, I may be forced to close it down by the end of this month [February 2015].

B&F: What role has historical research played in shaping your views on sexuality?

EH: Even the most superficial look at human history shows how relative our own present sexual customs, norms, and values are. It is therefore important to adopt a critical attitude toward all kinds of silent assumptions. Without this understanding, any history of sexology — or sexuality, for that matter — will remain superficial and useless. As for myself, I cannot point to specific historical studies that have inspired me. I did read the great study Die Prostitution (1912) by Iwan Bloch, one of the great pioneers of sexology. Unfortunately, he was able to complete only the first volume, which included a history of prostitution. The whole work would undoubtedly have become a classic, but, because of the early, untimely death of its author, it remained fragmentary. Nevertheless, I eventually became aware of the potential range of such studies through the provocative history of psychiatry by Thomas Szasz, The Manufacture of Madness (1970), and a German two-volume work by W. Leibbrand and A. Wettley Formen des Eros (1972). Of course, I also took note of the various writings of Michel Foucault and John Boswell, both of whom died before they could complete their sexologically relevant studies. But, quite apart from these “obvious choices”, I have always considered Max Weber’s Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (1904/5) a very interesting model to follow for historians of ideas. And, in my opinion, any history of sexology worth the effort is, above all, a history of ideas.

B&F: What do you think the existing historiography on sexology has overlooked or missed? Are there any areas of research, any individual groups or organisations, or researchers and writers that you think have been misunderstood or have not yet received sufficient scholarly attention? For instance, we are both concerned with the marginalization and misrepresentation of female sexuality in the field. What is your take on the importance of gender as an analytical category in the history of sexology?

EH: If one tries to support, as I do, the concept of sexology as a comprehensive, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary enterprise, one also has to support its contributing sub-disciplines, such as sexual economics, sexual sociology, sexual ethnology, sexual linguistics, etc. All of these are still neglected areas of research. This support is also appropriate for “sexual medicine”, “homostudies”, as the Dutch used to call it, and for “gender studies” as well. However, by themselves, these limited efforts cannot replace the unifying overview only a central standpoint can provide. Hirschfeld with his Institut für Sexualwissenschaft and Kinsey with his Institute for Sex Research claimed this central standpoint and insisted on covering all aspects of human sexuality. When the Kinsey Institute began to fear a break-up of its mission into unconnected sub-sections, it prophylactically renamed itself the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction. In vain: The break-up occurred anyway, and today Indiana University has an additional and separate Department of Gender Studies. Similarly, many universities now also support separate “Gay Studies”.

In my opinion, this loss of a unifying overview is regrettable and is, in fact, one of the reasons why — seen from a global perspective — sexology is now in general decline. As for making sexual medicine the anchor for sex research, I have said it time and again: Sexology embedded in a medical school is a stillborn child in a dead end street. Physicians must, ex officio, deal with patients and with sex offenders in so far as they show some pathology. However, most people are neither sick nor criminal, and thus the behavior of the majority of human beings remains uninvestigated. A medical Institute of Sexology cannot possibly undertake the necessary comprehensive research. It is like an Institute of Economics that studies nothing but stock market crashes and bankruptcies or an Institute of Geology that studies only earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. No one would take such half-baked institutions seriously.

B&F: Despite all of the historical research on sexology, there is still considerable uncertainty as to when sexology emerged, who was part of the sexological project, and so on. How do you think we can begin to chart the modern history of sexology?

EH: Despite the scientific focus of certain kinds of sexological research we might say that sexology — the study of human sexual behavior — is, first and foremost, a study of ideas. We can trace modern European and North American sexology back to the European “Age of Enlightenment”.

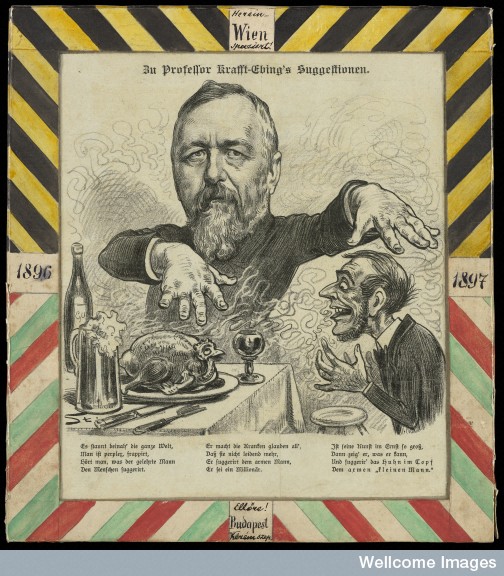

In Germany, I would argue that Wilhelm von Humboldt could be claimed as the “father of sexology”, since he sketched out, but did not carry out, an ambitious study of sexual behavior, which is little discussed today. Here he described the history of sex as a “history of dependency in the human race”, an idea that still needs to be explored more fully in the context of current scholarship on the history of sexuality. More famously, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and Richard von Krafft-Ebing are seen to be sexological pioneers, but, in my opinion, it was the very erudite Iwan Bloch, who pulled the many strands of ancient and modern sex research in all sorts of disciplines together under the unifying banner of Sexualwissenschaft (“sex science“ or “sexology”).

In England, Bentham and Malthus, the Neo-Malthusians, and later J. A. Symonds and Havelock Ellis are the most prominent names. In France, one may claim Rousseau, Voltaire and Diderot as sexological ancestors, finding their successors in Morel, Tardieu, Parent-Duchatelet, Rémy de Gourmont, leading up to Simone de Beauvoir and Michel Foucault. In Italy, Paolo Mantegazza may be considered the first sexologist, followed by Pasquale Penta. In Switzerland, Auguste Forel played a similar pioneering role. In the US, we find the first use of the English word “sexology” in a book title of 1867 [Elizabeth Osgood Goodrich Willard’s Sexology as the Philosophy of Life: Implying Social Organization and Government]. However, its meaning was different from the one we are using today. (The text was a philosophical-moralistic treatise on sex as a “universal life force”.) An explicit preoccupation with sexual behavior in the US is tied to the anti-masturbation campaigns of Graham and Kellogg and to the pernicious influence of the “super censor” Anthony Comstock, who loved to persecute doctors for providing women with “obscene material”, i.e. contraception information. As a counterweight to these repressive forces one can name Margaret Sanger, who encouraged important research, the educator Winfield Scott Hall, the gynecologist Robert Latou Dickinson, the hormone researcher and physician Harry Benjamin and the modern educator Mary S. Calderone.

These are just the most prominent names. Ultimately, I think it is impossible — and would be pointless — to pin the birth of this new science on a single individual or group of individuals, as it’s a very complex subject matter.

B&F: Your response speaks to what we think is a more “global turn” in scholarship on the history of sexual science (see e.g. the recent work of Howard Chiang, Veronika Fuechtner, Anna Katharina Schaffner, Jana’s research on Hirschfeld’s world journey and the relation between sexology and anthropology, or Heike’s edited collection Sexology and Translation, forthcoming with Temple UP). Perhaps you could also comment on how historians or other scholars interested in sexualities in the past have used your archive or what you hope they might be able to do with it in the future?

EH: My archives can offer no more than a collection of materials to serve as a starting point for going in all sorts of different directions. Both have been — and still are — regularly visited by scholars from different countries, but I rarely find out what they were looking for and what they did with it. Anyway, there remains quite a lot to be done. To give you just one example: My Archives contain all the papers (and their copyright) of the late “Dr. X” [including diaries and records of his sexual contacts as well as an extensive international correspondence]. It will take a team of scholars from a number of fields to analyse “Dr X’s” papers, but I have no doubt that this research would yield unexpected findings that would have a significant impact on future research in the field.

B&F: Your website includes a free and open-access curriculum in sexual health and states that its mission is “to promote, protect, and preserve sexual health”. How do you think the history of sexology can speak to present-day debates about sexual health and wellbeing?

EH: I wrote my sexual health curriculum of 6 courses (6 semesters) mainly for developing countries where libraries and universities may be rare and/or inaccessible for a variety of reasons. That’s why I am offering this curriculum in 7 languages. Sexual health and sexual rights are global issues today, and I try to provide as many people as possible with the scientific information necessary for a rational discussion of these issues.

B&F: Where do you see the future direction of sexology research? What contributions do you think literary or cultural scholars or researchers from disciplines other than History can make to our understanding of the history of sexology?

EH: As I already mentioned, in my opinion, the study of the economics of sex deserves top priority. If undertaken on the necessary grand scale, it could produce real eye openers for many people. Another interesting study would examine the implications of the present electronic revolution for human sexual behavior. This is a truly vast area begging to be investigated. Since we are now entering (or have already entered) the age of total surveillance, here are just a few urgent questions: What will happen to our sex lives, to our partner selection, to sex education, to the use of pornography, to prostitution etc.? We keep sending more and more “big data” to uncontrollable private corporations. How will they use this information? This is a topic of such overriding importance and enormous economic and political ramifications that I’d rather not try to discuss them here. I have, however, written about it on another occasion.

B&F: Is the modern history of sexual science still relevant today? In what ways?

EH: The scientific study of human sexuality has always been necessary and will, in the future, be more important than ever. The reason is a simple one: Sex is a political issue – always has been, always will be. In other words: Sex is an issue of power – who wields it, and who is forced to submit to it. We are talking here about the power of individuals, groups, tribes, nations, religions, legislators, media etc. etc. And, needless to say, in our capitalist system, power is closely associated with money. This, once again, shows how urgently we need an investigation of the economics of sex.

Heike Bauer is a Senior Lecturer in English and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. She has published widely on the history of sexuality, nineteenth and twentieth century literary culture, and on translation. Her books include English Literary Sexology, 1860-1930 (Palgrave, 2009), the 3-volume edited anthology Women and Cross-Dressing, 1800-1939 (Routledge, 2006), and the edited collections Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012, with Matt Cook) and Sexology and Translation: Cultural and Scientific Encounters Across the Modern World (Temple, 2015). She recently co-edited with Churnjeet Mahn a special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies on “Transnational Lesbian Cultures”, and is currently completing the AHRC-funded study A Violent World of Difference: Magnus Hirschfeld and the Shaping of Queer Modernity. Heike tweets from @Heike_Bauer.

Heike Bauer is a Senior Lecturer in English and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. She has published widely on the history of sexuality, nineteenth and twentieth century literary culture, and on translation. Her books include English Literary Sexology, 1860-1930 (Palgrave, 2009), the 3-volume edited anthology Women and Cross-Dressing, 1800-1939 (Routledge, 2006), and the edited collections Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012, with Matt Cook) and Sexology and Translation: Cultural and Scientific Encounters Across the Modern World (Temple, 2015). She recently co-edited with Churnjeet Mahn a special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies on “Transnational Lesbian Cultures”, and is currently completing the AHRC-funded study A Violent World of Difference: Magnus Hirschfeld and the Shaping of Queer Modernity. Heike tweets from @Heike_Bauer.

Jana Funke is an Advanced Research Fellow in Medical Humanities based in the Department of English and the Centre for Medical History at the University of Exeter. She has published several journal articles and book chapters on the history of sexuality, focusing in particular on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sexual science, literature and culture. She is the editor of a volume of previously unpublished archival writings by Radclyffe Hall entitled The World and Other Unpublished Works (Manchester University Press, 2015) and of Sex, Gender and Time in Fiction and Culture (Palgrave, 2011, with Ben Davies). She is currently working on a monograph on modernist sexualities and on a collaborative project on the cross-disciplinary history of sexual science. Jana tweets from @drjanafunke.

Jana Funke is an Advanced Research Fellow in Medical Humanities based in the Department of English and the Centre for Medical History at the University of Exeter. She has published several journal articles and book chapters on the history of sexuality, focusing in particular on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sexual science, literature and culture. She is the editor of a volume of previously unpublished archival writings by Radclyffe Hall entitled The World and Other Unpublished Works (Manchester University Press, 2015) and of Sex, Gender and Time in Fiction and Culture (Palgrave, 2011, with Ben Davies). She is currently working on a monograph on modernist sexualities and on a collaborative project on the cross-disciplinary history of sexual science. Jana tweets from @drjanafunke.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com