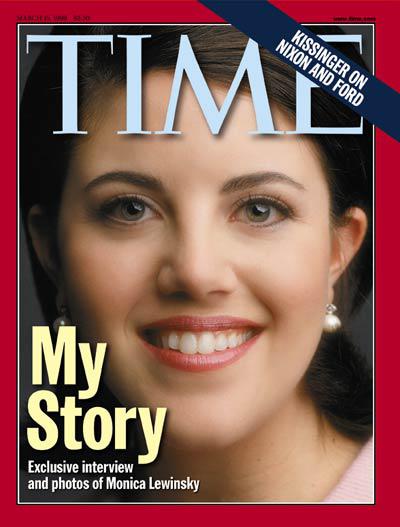

What happens if we take Monica Lewinsky at her word? How might engaging seriously with her claim that “I had the first orgasm of the relationship” shift our understanding of the politics of heterosexuality on the eve of the twenty-first century? The Lewinsky-Clinton affair has been read in many ways: as a cautionary tale about the dangers of the loss of privacy, as a moment when the rules of engagement of American politics fell apart, as an episode in the culture wars. For some critics, it is proof that second-wave feminism’s insistence that “the personal is political” nearly destroyed American culture. Focusing on Lewinsky’s narration of her experience offers a different perspective, exposing both the institutionalization and the instability of one feminist position: that mutuality could revolutionize heterosexuality. In seeking to explain herself, Lewinsky maintained that mutual desire, intimacy, and pleasure could transform the “president and the intern” into “a man and a woman.” But hers was a story that could barely be heard.

The value of mutual desire to a well-functioning heterosexuality was a fixture of American sexual ideology since early in the twentieth century. From companionate marriage in the 1920s to “togetherness” in the 1950s, it has been a truism that heterosexual relationships and marriages work better when women’s and men’s experiences are somehow “in tune.” Yet by the 1960s the meanings of mutuality were hotly contested, as the second-wave feminist critique of the “myth of the vaginal orgasm” revealed. Sex “experts” promoted mutual orgasm as a means of adjusting women to their reproductive destiny and to male authority. Women’s liberationists advocated a “true” mutuality that made female sexual pleasure a measure and mechanism of social equality. As the eruption of the feminist sex wars by the early 1980s suggests, this project turned out to be enormously divisive, as some feminists posited that certain sex acts—s/m, participation in pornography and prostitution, or particularly “degrading” practices such as anal sex or fellatio—were inherently inimical to mutuality and equality, while others sought to multiply the possibilities for female sexual pleasure even under conditions of inequality. This conflict structured Lewinsky’s understandings of the affair, as well as the responses to the scandal.

In fact, the feminist ethic of mutuality made Lewinsky a public figure, for it was embedded within the law of sexual harassment under which her affair with Bill Clinton came to light. In Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986), the U.S. Supreme Court defined sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination and established “welcomeness” as the measure of permissible workplace sex. The justices agreed that since what looked like consent under conditions of inequality might merely be acquiescence, welcomeness was a way of more robustly assessing the dynamics of a relationship: Was sexual conduct between coworkers agreeable and pleasing to both? Was there mutual desire? Since welcomeness could be difficult to challenge or substantiate, in 1994 Congress loosened federal rules to permit the introduction of evidence of “similar” conduct in sexual harassment cases. Similar conduct could include any sexual encounter in the workplace, even if there had been no allegation of unwelcomeness. As a result, when former Arkansas employee, Paula Jones, filed a sexual harassment suit against ex-governor Clinton, her lawyers were permitted to question him about his relations with Lewinsky.

Ironically, Clinton’s position, articulated in his deposition in the Jones case and maintained throughout the scandal, offered an unexpected take on the logic of mutuality. In official proceedings, he was confronted with a peculiarly narrow definition of sex, cobbled together from the federal law on sexual assault: “a person engages in sexual relations when the person knowingly engages in or causes contact with the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks of any person with an intent to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person.” He made use of the definition to his own advantage, consistently denying that he had “sexual relations” with Lewinsky: he had not touched the specified places on her body with the intent to arouse or gratify. He ultimately admitted to “inappropriate” intimacy that included fellatio, but mutuality was not its hallmark, Lewinsky’s pleasure was beside the point, and therefore it was not sex.

Lewinsky told a very different story about what happened between her and Clinton, describing in great detail a mutually satisfying and increasingly intimate heterosexuality, in which female and male pleasure could not be separated. In ten in-person sexual encounters, she claimed, there were nine acts of fellatio, but Clinton also touched her breasts with his hands or mouth on all ten occasions, manually stimulated her genitals four times, and pleasured her in other ways. He wanted to arouse her and one time had “focused [on her] pretty much exclusively.” If he came on two occasions near the end of the affair, he brought her to orgasm in three of their encounters, and she had at least 7-10 orgasms (not counting phone sex) over the course of their affair. Indeed, his orgasms were proof of their mutual caring, since he allowed himself to ejaculate only because it was so important to her as a path toward greater intimacy. Clinton had presented their touching as one-sided and limited, but Lewinsky believed that their relationship was much more than “sexual servicing,” even if it was also frustrating, disappointing, and in the end, marked by betrayal.

This account of mutuality mediating the inequality (of age, status, and power) between partners was met on almost all sides with disbelief, not least because of the prominence of oral sex within their sexual repertoire. Even as cunnilingus and fellatio became increasingly ordinary practices for Americans, fellatio, particularly if “unreciprocated” (i.e., not accompanied by cunnilingus), stood as a degrading act of subordination. It may have shed its older reputation as a “perverted” practice indulged in only by prostitutes and homosexuals, but it retained its gendered meanings as an act that confirmed the social inferiority of the individual who gave but (allegedly) did not receive pleasure. It was this logic that simultaneously allowed Clinton’s lawyers to suggest that Lewinsky had invented a tale of mutual touching in order to “avoid the demeaning nature of providing wholly unreciprocated sex,” and prompted radical feminist Andrea Dworkin to describe the oral sex in this relationship as a “fetishistic, heartless, cold sexual exchange” that placed Lewinsky in a “state of submission.” These interpretations left little room for Lewinsky’s attempt, in scholar Maria St. John’s words, to “rewrite the history of heterosexual fellatio” by declaring that fellatio could be an intimate, passionate, and mutual act between “sexual soulmates.”

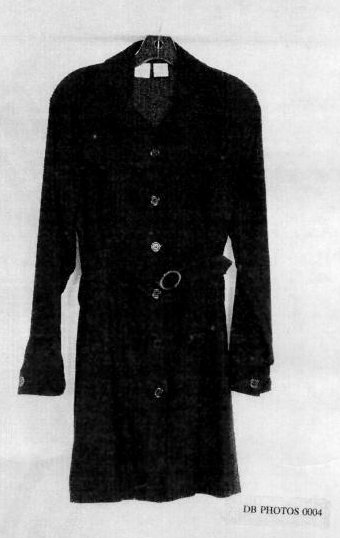

Lewinsky’s claims of mutuality also were undermined by Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr’s efforts to impeach the president, even as they were crucial to demonstrating that Clinton had lied under oath. Her testimony about mutual touching structured the Starr Report, but the decision to make central to his case her blue dress—stained with Clinton’s semen during one of their last trysts—contributed to public perceptions of Lewinsky as simply providing a sexual service. Starr forced her to produce the dress in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Relatively new DNA “fingerprinting” technologies made it possible to analyze the stains and link them with “a reasonable degree of scientific certainty” to Clinton. While these technologies did prompt the president to admit to “wrong” (but still not sexual) contact with Lewinsky, the dress’s role as physical evidence attested only to his arousal and, in that sense, was irrelevant to the question of perjury. Nonetheless, it was featured as “Exhibit No. 1” in the Starr Report.

The forensic uses of the blue dress silenced Lewinsky’s testimony and refocused attention on phallic pleasure. In a sense, the dress took on a life of its own. It stood in for Lewinsky herself, inviting spectators to imagine her as a body to be used rather than a desiring subject. Further, the dress was portrayed in ways that linked to broader characterizations of her as not serious, not smart, and not qualified. Even though Lewinsky had been a salaried federal employee from the affair’s beginning, she was widely represented as concerned more with consumption (obsessed with food, shopping, and sex) than with production or work. Fantastical descriptions of the dress as a cocktail dress, “a little blue dress,” “Monica’s Love Dress,” and many variations on the theme, contributed to this portrayal. Even Starr’s assistant Karin Immergut, whom one might expect to know something about the matter, questioned Lewinsky about “the day you wore the blue cocktail dress.” Lewinsky retorted, irritatedly, “It’s not a cocktail dress… I’m a little defensive about this subject… It’s a dress from the Gap. It’s a work dress. It’s a casual dress.” As Lewinsky described it, the dress was a utilitarian item, one that situated her in the respectable arenas of work and family. Within the scandal, however, the dress confirmed that she was, variously, a seductress, an immature child (“I’ll never wash it again!,” she was alleged to have said), a victim, or a bimbo, anything but what she claimed to be: a young working woman who happened to have had a difficult but also passionate, exciting, and mutually welcome relationship with her boss.

Over the past two years, Monica Lewinsky has reinvented herself as a public intellectual, writing and speaking about her experience in the 1990s in order to “have a different ending to my story.” Lewinsky did not feel shamed by her sexual interactions with Clinton, but as she said in 2014, becoming known as “America’s premiere blow job queen” constituted public humiliation on a global level. That reputation depended on ignoring, disbelieving, or silencing her account of her sexual pleasure. We need not accept that Monica Lewinsky’s experience in the relationship was the same as Bill Clinton’s to ask why giving it voice subjected her to almost universal ridicule and contempt, even among those who imagined themselves to be her defenders. While there was more feminist support for Lewinsky than has been acknowledged, that “support” as frequently took the form of naming her a victim—of Clinton’s “notorious persuasiveness” or of her own romantic delusions—as honoring her sexual choices. Many second-wave feminists may have thought mutuality was a good thing—they even succeeded in enshrining it in law—but they had trouble believing that it was possible in a world structured by gender inequality.

Even more recently, in a context of heightened concern about slut-shaming and cyberbullying, some dismiss Monica’s story of mutual desire, pleasure, and intimacy as a chimera. Sociologist Chrys Ingraham, for example, identifies Lewinsky as an example of the heterosexual imaginary, a young woman whose self-understanding was distorted by ideologies of romantic love that distract women from the exploitative social relations of patriarchal heterosexuality. Lewinsky’s continuing efforts to regain control over her own narrative have been met with mixed results: her Ted Talk was highly praised, but recent public opinion polls reveal that she remains a scorned figure, and that she continues to be used as an instrument of partisan politics rather than recognized as a speaking subject. Remembering that her orgasm came first is unlikely to change these political realities, but it serves as a reminder that her humiliation helped silence a particular feminist politic about the possibilities of some women’s sexual self-determination within apparently unequal systems of sexual exchange. It remains to be seen if we’ve yet arrived at a moment when this story can have a different ending.

Andrea Friedman is an Associate Professor of History and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. She is the author of two books: Citizenship in Cold War America: The National Security State and the Possibilities of Dissent (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014) and Prurient Interests: Gender, Democracy, and Obscenity in New York City, 1909-1945 (Columbia University Press, 2000). She is currently at work on a book on sexual politics during the Clinton presidency.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com