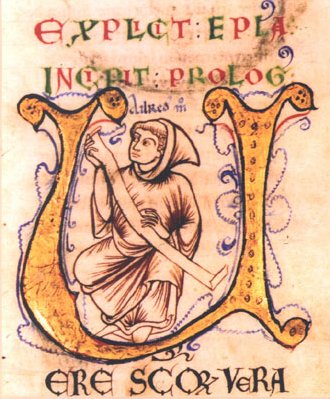

In medieval North Yorkshire, around 1160, Aelred of Rievaulx finally responded to his sister’s request for a guide to being a good recluse, writing the De institutione inclusarum or ‘Rule of Life for Recluses’. Alongside advice about when to pray and when to fast, he includes lengthy warnings about the dangers of contact with men, and the great prizes available in heaven for those who remain virgins. He also warns her about how easy it is to fall into sin. She could even lose her virginity – and her heavenly rewards! – without having sexual relations with another person, for ‘virginity is often lost and chastity outraged without any commerce with another if the flesh is set on fire by a strong heat which subdues the will and takes the members by surprise’.

For Aelred, sexual desire is a hot flame that could sweep through his sister’s body without warning – and without her consent – to surprise her ‘members’. These same members, he continues, were consecrated to God when she became a recluse and she ‘should blush if her virginal members are stained by even the slightest movement’. This is slightly strange advice to give a woman. How exactly will her ‘members’ move? For that matter, what are her ‘members’?

Aelred tells his sister a story about a ‘certain monk’ that sheds some light on this description. The translator of the De institutione inclusarum has identified this monk as Aelred himself. When he talks about his own sexual arousal, he uses strikingly similar terminology to his discussion of his sister’s desire. In the past, he tells her, he asked Jesus for tranquillity because his sexual temptations were all-consuming. His prayers were successful for a while, but ‘while the irregular movements of the flesh died down for a little, his heart was beset with forbidden affections’. The irregular movements of Aelred’s disobedient flesh are clearly reminiscent of the strong heat that might take his sister’s members by surprise; sexual desire is something that happens to them, involuntarily. Aelred’s unwanted erections – the movements of his members – are mapped wholesale onto his sister’s body.

As well as assuming his sister’s sexual arousal functions in the same way as his own, Aelred also uses metaphors for virginity that blur the distinction between his and his sister’s embodied experiences of sex. When he compares his sexual history with his sister’s, he praises her for holding on to her virginity and laments the loss of his own chastity. When ‘tempted’ or ‘attacked’ by lust, she remained chaste, while Aelred explains that he ‘freely abandoned myself to all that is base’. Comparing her virginity to ‘a precious treasure you bear in how fragile a vessel’, Aelred sets up his sister’s body as a container full of a precious substance that could be lost forever. His description of his own lost virginity functions in a similar way, as he cries out:

O sister, how much more happy is the man whose ship, full of merchandise and loaded with riches, is brought to a safe homecoming by favorable winds than he who suffers shipwreck and barely escapes death with the loss of all? So you exult in these riches which God’s grace has preserved for you, while I have the utmost difficulty in repairing what has been broken, recovering what has been lost, mending what has been torn.

His body is imagined as a ship filled with precious cargo, and the loss of his virginity as a shipwreck that tips this treasure out into the sea. As his sister remains chaste, she retains her riches within the intact vessel of her virginal body. The metaphor of the loss of virginity as a loss of wholeness is not tied to the penetration of the female body in a heterosexual sex act. Rather, Aelred sees any participation in sexual behaviour or even lustful thoughts as a destruction of the integrity of the chaste Christian body.

Aelred also gives us some insight into the ‘forbidden affections’ with which he was tormented – and again suggests that his sister might suffer from the same kind of sexual desire. Using the first person plural, he tells her: ‘we must keep within due limits those things which provide material for vice: eating, sleeping, bodily relaxation, familiarity with women and effeminate men, and sharing their company’. Here we get a list of Aelred’s temptations that implicates both him and his sister in what we would now call homosexual desire. He must avoid women and effeminate men in order to remain chaste, and so must she – he imagines her arousal in terms of his own. Aelred’s text challenges a strict binary view of sexual desire and temptation in a way that was unusual at the time, as well as today, and gives us a fascinating insight into his understanding of the similarities between male and female experiences of sex and sexual desire.

Kathryn Maude is a PhD student in the English Department at King’s College London, working on texts addressed to women between 960 and 1160. She starts work at Swansea University in September. She tweets from @krmaude.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

One Comment